by Colt McAnlis

Where do all the bytes come from?

Great question Dion! I will answer it, and not just because you’re my new boss, but because it’s a good question. (but also because you’re my new boss.)

I want to set something clear here though : we’re not really comparing Apples-to-Apples, so let’s define some technologies first.

How Mario Works

So let’s talk about how the original Super Mario game worked, from an asset perspective.

The original NES console was only designed to output images that were 256 wide by 240 high; meaning that the final image that needed to be displayed to the screen was 180kb in size.

Besides that, the NES only had 2kb of RAM. A cartridge itself could could hold 8k to 1mb of game data. So, there was no way to fit the entire game’s contents into main memory. Basically, a subset of the 1MB cartridge data must be loaded into the 2kb RAM and used to render the 180kb screen. How does one achieve that?

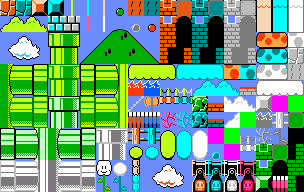

Sprite sheets contain small tiles of graphics, that are re-used over and over again. For example, below is a remake of the original super mario sprite sheet:

Each small 16x16 pixel square represents a “tile” and artists would string these together to create the actual levels. The levels themselves, just became a giant 2D array of indexes into the sprite sheet. (I talk about this in a lot more detail in Lesson 3 of my HTML5 Game Development course @ Udacity, or in my book HTML5 Game Development Insights.) Tack on some Run-Length-Encoding, or some basic LZ77, and you get a fairly compact format for levels.

So with concepts like tile-sheets and sprite-sheets, we can use a small set of images to create large scenes & worlds. This is generally how most games work. Even 3D games will have a set of common textures that are applied multiple times and places throughout the game itself.

Now let’s talk about generic image compression.

How Images are compressed

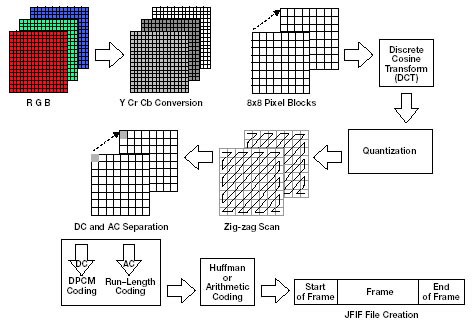

Here’s the “not fair” part of this comparison. Generic image compression algorithms have no domain knowledge about the pixels inside of them. JPG, PNG, WebP have all been designed for photos and not so much game screens. The result is that for a given 16x16 pixel block, these algorithms assume it’s unique among the image; Besides some color quantization, there’s no real logic added to determine if another 16x16 block could be an exact duplicate of the current one. This generally means there’s a lower-bound on how a given block of data is compressed.

For example, JPG breaks a given image into 8x8 pixel blocks, converts the RGB color space into the YCbCr version, and then applies Discrete cosine transform on them. It’s only after this step, does a lossless encoder come along, and see if it can match up common duplicate groups using DPCM, or RLE.

So, the only place where two blocks might get compacted into 1 block, is if their post-DCTd version is identical, and RLE can make stride recommendations. This doesn’t happen that often.

Despite its other flaws, PNG is much better in this regard. PNG compression is entirely lossless, (so your image quality is high, but your compression savings are low), and based on the DEFLATE codec, which pairs LZSS along with Arithmetic Compression. The result is that long runs of similar pixels can end up being cut down to a much smaller size. This is why an image with a very uniform background will always be smaller as a PNG instead of a JPG.

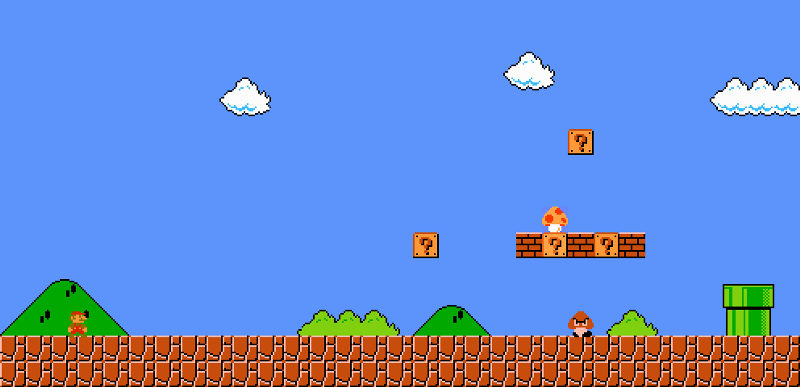

The below image is a 5.9kb PNG file, while the JPG image is 106kb

Apples vs. Dragonfruit

My point here is that it’s kinda unfair to compare game content to a single image on the internet.

From the game side, you start with a small set of re-usable tiles, and index them to build up your larger image, we can do this, because we know how the game is going to be made. On the other side, JPG/PNG/WebP just tries to compress the data it can find in local blocks, without any real desire to match repeated content. Image compression is clearly at a disadvantage here, since they don’t have prior knowledge of their data space, they can’t really make any expectations about it.

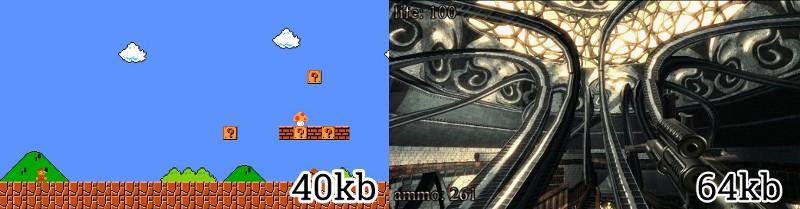

I mean, consider The Demo Scene which is super big on this sort of thing. They can cram 30minutes of an entire 3d shooter into 64kb because they understand and know so much more about their data.

It just goes to show, with the right amount of foreknowledge about your data, you can do great things with compression.

Looking forward.

Obviously, we’ve grown up since the 256x240 displays of the NES days. The phone in my pocket has 1,920 x 1,080 display pixels @ it’s 5.2” size, giving it ~423 pixels per inch density. To compare that in the same number of pixels that’s ~33 super-mario screens, or rather, 8MB of pixel data. I don’t think anyone’s surprised that screen resolutions are increasing, but it also comes with the need for more data.

This is something I’ve been harping on for a while now. While we get bigger displays, the content channels need to up their resolution outputs in order to still look good on our higher-density setups (otherwise, we get scaling blurryness..). This of course, causes our video game packages to grow in size, our web-pages to grow in size, and even our youtube streaming videos to grow in size. Basically, we’re sending more data to smaller devices simply due to screen resolution. Which, for the next 2 billion folks in emerging markets, on 2G connections, is like the worst idea ever.

But I digress. That’s a different post.

If this article was helpful, tweet it.

Learn to code for free. freeCodeCamp's open source curriculum has helped more than 40,000 people get jobs as developers. Get started